Why a career in statistical ecology?

I have been interviewed recently by Lise Viollat who’s preparing a documentary for our national research group in statistical ecology. I have written my two cents answers to her challenging and very relevant questions. Thank you Lise for the interview !

Can you introduce yourself? What is your job about? Your background?

My work is motivated by questions on the ecology of large mammals, and large carnivores in particular (wolves, bears and lynx).

What questions ? Very basic questions at first glance: How many animals? Where are they? How to explain trends in population abundance and species distribution?

These questions might seem simple, but the issue is that large carnivores are difficult to see in the field. We need methods to sample these populations, to manage uncertainties in counting, in detecting individuals and species, and to predict as well, where and how many. This is where statistical ecology comes in.

I am what you might call an ecological statistician, and I work for the National Centre for Scientific Research.

I have a rather standard background. I studied mathematics up to Bachelor’s degree. A degree that I repeated, I still had nightmares about it until recently. Then, from the Master’s degree onwards, I turned to applied mathematics and statistics. I embarked on a PhD in statistics applied to ecology, and to the dynamics of animal populations, with the estimation of survival and dispersal. As a post-doc, I spent time in England and Scotland to see what it was like elsewhere, to build my own research network, and to learn English.

Once recruited, I became increasingly interested in evolutionary ecology and conservation issues. I also worked more and more on issues related to large mammals, and species that interact with human activities.

To better understand these interactions, we need the human and social sciences. So I went back to studying sociology. I took a few courses, but I couldn’t go all the way to the Master’s degree. I am still learning on the job.

What is ecology for you?

I am certainly not the right person to answer this question, I never studied ecology at university. I learned from my students and colleagues, and on the job.

I like definitions, so I’m going for it. Ecology is the study of the processes that influence the distribution and abundance of species, the interactions between these species, and the interactions between these species and their environment. Maud Quéroué’s thesis is an example of the study of these interactions between species using new statistical models.

It’s the science of interactions in a nutshell, and that’s what I like about this discipline. Between species, between species and their environment. By species, I also mean humans. And here we come back to this idea of mobilising ecology, human and social sciences, and the study of socio-ecosystems in which we mix ecology, politics, economics, sociology and anthropology. Gilles Maurer’s thesis is an illustration of this approach, and combines demography, genetics, economics and anthropology to study the relationship between Asian elephants and humans.

Finally, when we talk about ecology, we must understand it in a broad sense, with the idea that we are also talking about the evolutionary processes that contribute to explaining variability in biological systems. The theses of Marlène Gamelon and Mathieu Buoro are examples of work combining ecology and evolution to better understand the dynamics of animal populations.

How would you define statistical ecology? And modelling?

In statistical ecology, statistical is the adjective that qualifies the noun ecology. It is ecology that motivates, that asks the questions. This does not make statistics a mere toolbox, but you have to accept the statements of ecology to make relevant statistics.

Coming from mathematics and statistics, this is something that did not come naturally to me. In statistics, one often sees the data from ecology as the numerical application to show that the statistical method works in the real world (often in addition to simulated data).

I learned the importance of motivating statistics by ecological questions from Jean-Dominique Lebreton, one of my thesis directors, who himself got it from Jean-Marie Legay who thought a lot about the place of modelling in biology, and interdisciplinarity.

Statistical ecology therefore means applying and above all developing statistical methods and tools to answer questions in ecology. In France, the scientific community meets on these themes in the statistical ecology research group which we created in 2014.

Statistics in general is the science of collecting, analysing and drawing conclusions from data. All three are important for ecology. How we collect data to test ecological hypotheses. How we analyse it. And how you interpret the results.

It is at the analysis stage that models are mostly used. A model in this context is an abstraction of reality, based on what is known, and is used to extract information using probabilities. An example of a statistical model is a simple linear regression in which we try to pass a line through a scatter plot to explain a trend.

How is statistical ecology useful?

Why is it important to ask the questions “where are the species?”, and “how many animals are there?”? The species we study are in contact with humans and their activities. Fishing activities for bottlenose dolphins in the Mediterranean, for example, or sheep farming for wolves in France, to take another example.

In this context, I would say that statistical ecology and modelling serve three main purposes. To understand, to predict, and to help in decision making.

I’ll take the example of the wolf, on which we do a lot of work with colleagues from the French Office for Biodiversity.

First of all, we need to understand. We need to know the factors that explain the distribution of the species, this is information that allows us to establish the conservation status of a species. It was Julie Louvrier’s thesis that showed that the species is plastic and how it has recolonised the country.

Predicting then. Julie also showed that it was possible to predict the short-term dispersal of the species with a mathematical model that was fitted to the data. As another example, Nina Santostasi in her thesis evaluated the effectiveness of different management scenarios for hybridisation between dogs and wolves in Italy.

Finally, informing the management decision process. The species is managed by the French state, and it is on the basis of the numbers we produce thanks to statistical ecology that the maximum number of culls is established each year. This was Lucile Marescot’s thesis. We also need to know the effect of shooting on wolf predation of domestic livestock, a complex problem in spatial statistics. This is Oksana Grente’s recently defended thesis.

To sum up, there is a lot of discussion about biodiversity and ecosystem services, and therefore about the interdependence between humans and nature. A connection that is increasingly forgotten, to quote a theme dear to Alix Cosquer who is part of our team and works in environmental psychology.

In this context, statistical ecology is used to understand, predict and inform decision-making on the interactions between species, animals and humans, and their environment.

Why did you choose this career?

Several reasons, in no particular order.

- It is an incredible privilege to be paid to be a researcher, especially as a civil servant. Personally, I did not want to experience the difficult working conditions of my parents. Professionnaly, this status offers good conditions for doing our job. A permanent position allows us to work as a collective. This is an important point because research is an adventure involving several people, a team adventure; you don’t achieve anything, or not much, when you work alone (at least for me). You don’t do good research by pushing for

more competition.

Our status also allows us to take a long view, a long view that is essential for quality research, research that also serves society. Our work on the wolf, which I mentioned, began more than 10 years ago! This long time frame is being undermined by the precarization of employment which is hitting the research world hard, with more and more fixed-term contracts, and I am worried about the consequences for the younger generation of course. More competition. More administration. More excellence. Go fast. Quantity. Productivity. Fewer jobs. Fewer resources. Research and teaching are managed like a company, we have to optimise, rationalise, students are customers. It can’t work. Sorry, I’m going astray…

-

Another reason I chose this career is that I wanted to tackle applied problems, which could have concrete applications for people, for society. Or at least to contribute a little bit in that sense. To be useful, basically.

-

Another reason is that it is very (very) rewarding to accompany and support the new generation of scientists. It’s exciting, I love to walk the path with those who are embarking on a master’s degree, a thesis or a post-doc.

-

Finally, this job allows you to be on the move all the time in your head. You learn all the time. You are constantly intellectually stimulated. I love that.

Do you have to be good at math to do this job?

We all have a maths hump. The sense of number, of counting. It is by training this sense that we improve, that we become better at maths. Like with a musical instrument.

The main obstacle is surely the language, because maths is also a language. Again like with music. You have to learn it to read it, to write it, and to understand what people who do it say to each other. With some efforts, you can really enjoy yourself.

What’s important to realise is that you can use maths in ecology at any level. From the simple rule of three, which I have mastered to the use of stochastic differential equations, which I have not understood. Everyone can find what they are looking for, and do relevant research. For statistics I recommend David Spiegelhalter’s book which introduces the discipline in a very accessible way.

What do you like about what you do?

First of all, it’s the people I work with. My biggest motivation comes from my students. I want to work with them, to exchange, to interact. It’s all about interactions. It’s also the people in our team. I’m learning all the time. And it’s the people in the statistical ecology community in France and abroad. It’s a community that doesn’t take itself too seriously, but that does serious and exciting research to answer the big questions about the biodiversity crisis. It is also very nice to feel part of a community. By the way, we are organising the next GDR Ecologie Statistique days in Montpellier at the beginning of April 2022, don’t hesitate to join us!

The second thing, as I have already mentioned, is the fact that you are always on the move intellectually. You learn, you try things out, you explore, you play, you write, you read, you think, all the while feeling useful at your level in the construction of knowledge.

The third thing is sharing. Sharing knowledge by accompanying the students first of all, as I mentioned. And teaching too. I don’t do much as I’m already having trouble keeping my head above water with my job as a researcher. I admire my colleagues at universities who do two jobs, they are researchers and teachers! In sharing, I also include workshops that we offer over several days during which we train folks in statistical ecology methods. These workshops are free and video recorded so that as many people as possible have access to them.

What are the future challenges of ecology?

I have no idea! I don’t really consider myself an ecologist. The only things that come to mind are related to our research topics, of course. I think about biodiversity conservation. How do we find a balance, and a sustainable balance, between our activities and the nature around us? This means understanding better the interactions between human and non-human actors, why these interactions can lead to conflicts and how to resolve them. It also means working on complex systems, the so-called socio-ecosystems, and therefore opening up ecology even more to the human and social sciences.

And the future challenges for statistics and modelling?

I’m not necessarily more comfortable talking about future challenges for statistics and modelling, but we’ve thought about it a bit with colleagues from the GDR EcoStat, so I’m a bit less dry than for ecology. I see three.

-

Firstly, the modelling of socio-ecosystems. There is a need to integrate different disciplines in agent-based approaches (economics, geography, ethnology). The question is how to use modelling approaches to estimate the many quantities in these complex models.

-

We have an explosion of technological means deployed at all scales of organisation. I am thinking of camera traps, environmental DNA, GPS, drones, aerial or satellite photos, etc. We are faced with a huge amount of data from which it is often difficult to extract the relevant information. The second challenge is therefore that of massive data, and the development of approaches that allow us to learn from this data and automate tasks that become impossible for humans to do. I am obviously thinking of machine learning, and deep learning in particular.

-

The third issue is predictive ecology. How can we predict ecological phenomena? This requires the manipulation of large-scale systems that couple ecology and physics, for example, or the ocean and the atmosphere, to take another example. It also requires thinking about how to propagate uncertainties throughout the analysis, right up to the prediction.

Is there a tool, a school of thought, a discovery that has changed everything for you in your field?

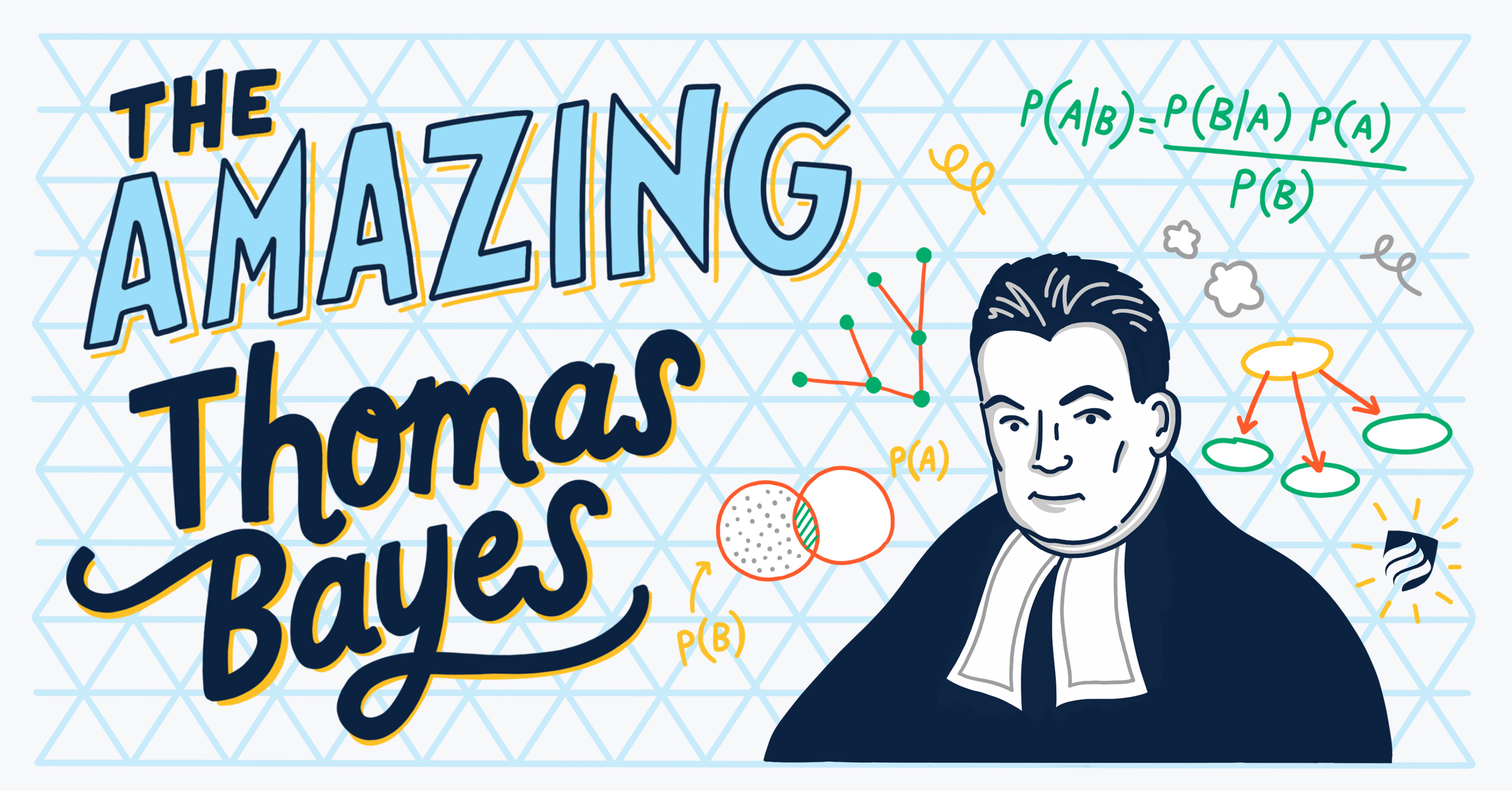

Yes, clearly! It is the introduction of Bayesian theory in the early 2000s. I discovered this theory as a post-doc in England and then in Scotland with my colleague Ruth King and others.

What is the Bayesian theory? The idea is to update the a priori knowledge we have of a biological system with the data we accumulate on this system. This a priori knowledge can be seen as the confidence we have in a hypothesis, and the Bayesian theory allows us to update this degree of confidence thanks to the data. The Bayesian theory allows us to formalise the natural way of reasoning, to induce the chances that a hypothesis is true or false.

The Bayesian theory is used everywhere in science, but also in the everyday world, for example in medicine to make a diagnosis, in computer science to calibrate the anti-spam of your e-mail, in finance to manage stock portfolios, and it even allowed Alan Turing to crack the Enigma machine which allowed the Germans to communicate by coded messages.

The strength of the Bayesian theory also comes from the fact that it comes with very powerful algorithms to put it into practice. Very powerful in the sense that we can use increasingly complex models that are closer and closer to what we know about the species we are studying, models that we could not dream of using before.

To give you a concrete example, I can think of one. In ecology, we often try to model the distribution of species. This requires data on large areas to be sure that we have sampled all the habitats that are favourable or unfavourable to the species. This is difficult to do with a demanding and expensive scientific protocol. We can see that participatory science makes it possible to sample large areas at lower cost. But the data are biased because if we see a lot where there are observers, that doesn’t mean that where there is no one, the species isn’t there; it simply means that where there are people, the species is detected. Bayesian analysis makes it possible to combine these different types of monitoring to quantify distribution by combining the advantages of both types of monitoring, unbiased data from scientific protocols, and wide spatial coverage from participatory programmes. This is the thesis of Valentin Lauret.

Don’t get me started on Bayesian theory, I teach it in our Master’s programme and to PhD students in our doctoral school and I can’t get enough of it!

Could you give an example of your work?

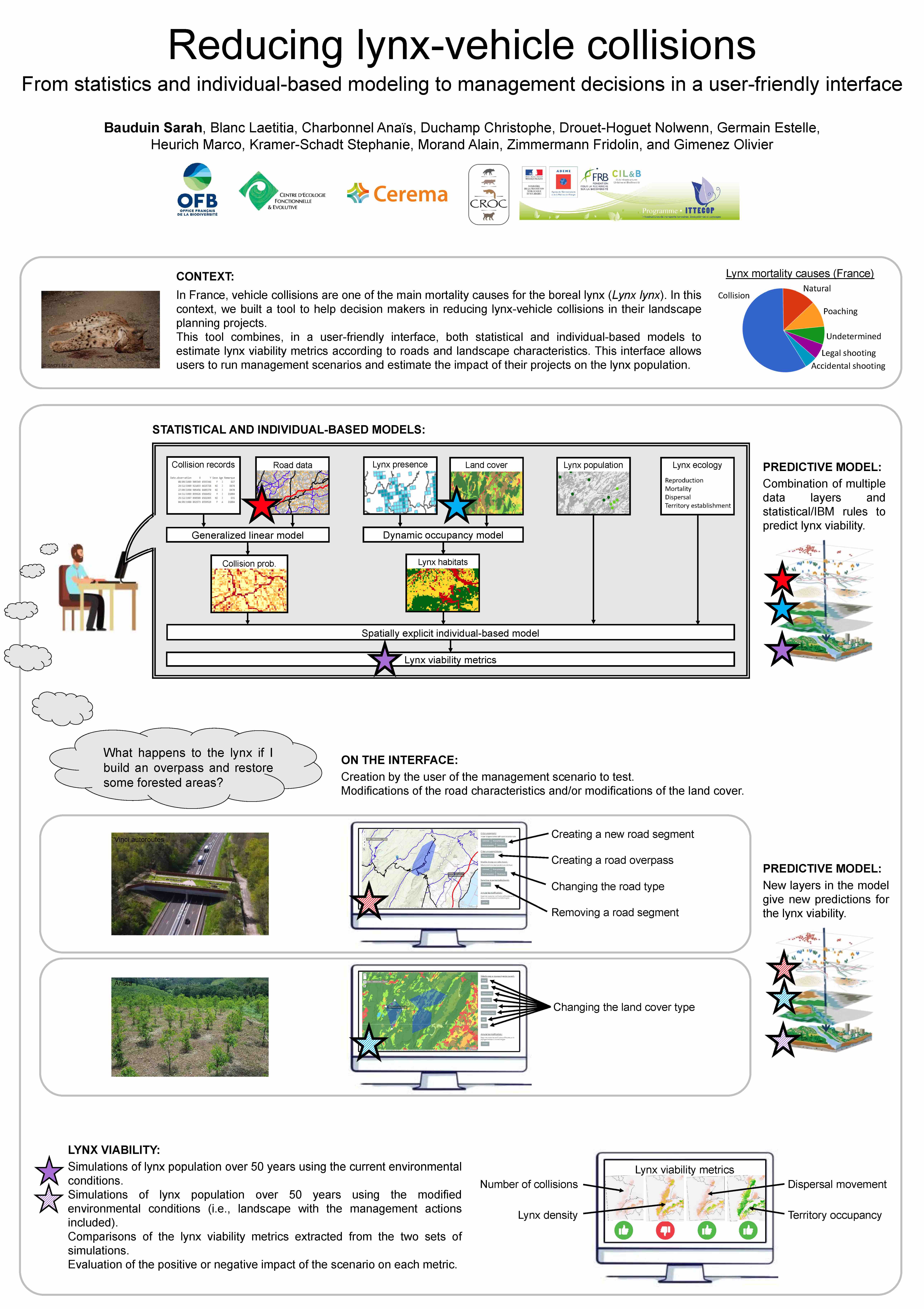

Recently, we’ve been working a lot on the lynx in France. The main cause of mortality for the lynx is collisions with cars. A major challenge is therefore to find ways of reducing this mortality by collision. We have developed a model that allows us to evaluate scenarios to reduce this mortality. For example, building a wildlife crossing, basically a tunnel or a bridge through which animals can cross the road without risk. We wanted this tool to be used by those involved in the lynx dossier, and in particular by the regional government. We therefore encapsulated all the modelling components in a software that can be used by non-specialists. Everything is done in R, so it is open and reproducible!

Why did I choose to talk about this project specifically?

Firstly because it is a project that mixes different types of modelling, statistical and computer science, different disciplines with ecology and statistics, and sub-disciplines of ecology with landscape ecology, movement ecology, and population dynamics.

Secondly, because it was a project in which I questioned myself a lot. We chose to show the modelling to the actors with workshops where we presented the models and where we were put in place. The stakeholders had very high expectations, both in terms of the models, their use, the outputs, the long-term maintenance of the software and the updating of the data. In the end, co-construction enabled us to be much more relevant than if we had done the same modelling work in the laboratory.

Also in human terms, it is a project that ended well, since the post-doct who was the link between the different partners and who did most of the work, Sarah Bauduin, was recruited by the French Office for Biodiversity.

Finally, it is a project that opens up other research questions, with a focus on connectivity problems due to fragmentation by land transport infrastructures (car and train). This is Maëlis Kervellec’s thesis which she has just started.

Any message for young people who might be interested in this route?

You mean the old fart’s message to the younger generation? I always find it difficult to give a message, to give advice. Especially because for me it worked, but clearly I was lucky, very lucky. What worked for me will not necessarily work for others. In that sense my message and my advice are not worth much.

I’m going to cite Ted Lasso, and I’m going to say: be interested, read, ask questions, be curious about what other people are doing, and why they are doing it. Don’t listen too much to the advice of old people, and make your own way.

And have fun, don’t take yourself too seriously!

An anecdote to share?

A rather positive consequence of confinements. It’s the story of a training course in population dynamics that we offered in 2006 with about 30 participants at that time. We’re going for a reboot next year with two colleagues and friends of the team, Aurélien Besnard and Sarah Cubaynes. One tweet and a few messages to some mailing lists later, we have 2315 subscribers after 15 days! We’re not sure how we’re going to manage all these people, but it’s very exciting! Many of the people who have signed up come from countries where access to knowledge is difficult for many reasons. So we’re doing a free, online course, and we’re recording it. That’s where I’d like to go, more knowledge sharing. It sounds a bit grandiloquent, but there is a great need for biodiversity conservation.

📢👋 Together with @SarahCubaynes and @abesnardEPHE we will be giving a 2-day introductory workshop March 21-22 on quantitative methods for population dynamics in R #rstats Join us 🥳 It's online and free of charge 😉 You just need to register https://t.co/I5sNS5kDOo Please RT 😇 pic.twitter.com/rkw8JWZBJi

— Olivier Gimenez 🖖 (@oaggimenez) October 11, 2021